This blog post is by William Rodick, Ph.D., P12 Practice Lead with The Education Trust, a Unite Against Book Bans partner.

Amidst a continuing rise in book censorship, we must refocus on what kids need, and what kids need are richer and more complex books in schools. Some argue that there is somehow too much diversity and books contain too many perspectives, but that couldn’t be further than the truth.

As we are witnessing a literacy crisis and historic drops in student achievement, better representation in our classroom books would help all students achieve higher outcomes. The unprecedented rise in school and library book challenges, however, threatens to exacerbate declines in student interest and proficiency in reading. It is imperative that education, publishing, and parenting communities come together to fight against unconstitutional and discriminatory book censorship. We must collectively push in the opposite direction, against banning books and towards greater representational balance in school curricula.

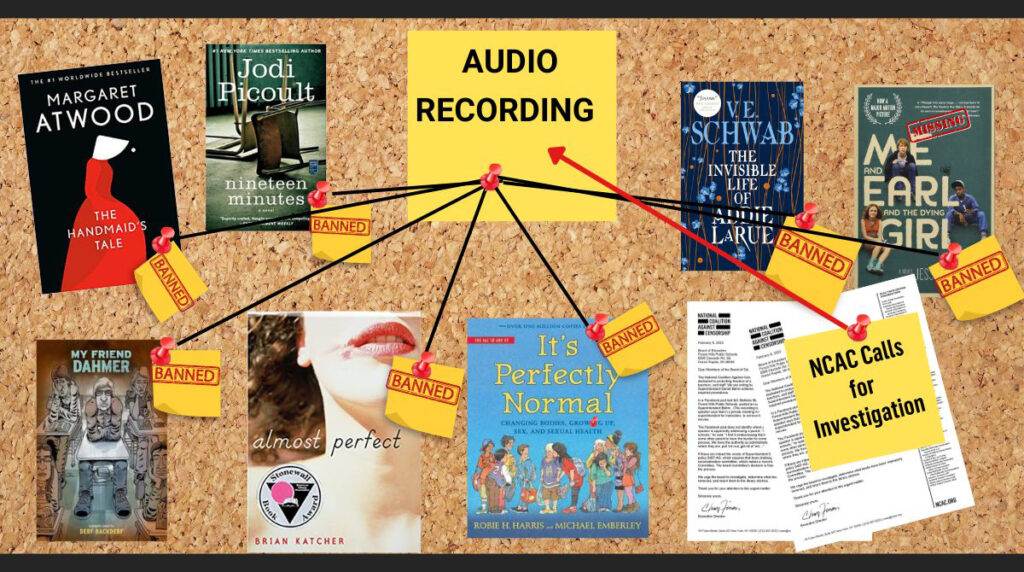

According to, there were 3,362 book bans over the 2022-23 school year, an increase of 33 percent over the year before. Nearly a third of those books include characters of color and themes of race and racism, and nearly another third represent LGBTQ+ identities. Examples of banned books include I Am Rosa Parks, I Am Martin Luther King, Jr., The Bluest Eye, All Boys Aren’t Blue, and The Hill We Climb.

The fact is, there has always been representation in curricula — and that representation is predominantly white. For EdTrust’s recent report, The Search for More Complex Racial and Ethnic Representation, my colleague, Tanji Reed Marshall, Ph.D., and I examined racial and ethnic representation in the books used in U.S. curricula in English Language Arts. We found that almost half of the people of color centered in the 300 books we analyzed were one-dimensional, portrayed negatively, or did not have agency. When books did include groups and cultures of color, they often used stereotypes, disconnected culture from individual people, or portrayed those groups as less than or unequal to others. And when historical and social topics were included, they were almost always sanitized, told through a singular perspective, or disconnected from the structural realities that help students make meaning of the reading.

While some publishers, state boards, districts, and educators have worked hard in recent years to increase representation in curricula, there is still much more to be done. To prepare all students to function in a multicultural world, to build intellectual skills for addressing tomorrow’s problems, to push back against a growing censorship movement, and to advocate for authentic racial representation in books, we offer six recommendations to move curricula development toward representational balance:

- Challenge dominant norms and singular perspectives

- Expand publisher and educator definitions of cultural relevance

- Ask a new set of questions about representation

- Consider how texts sit in conversation with one another

- Expand educator choice in curated materials

- Provide professional learning to all curriculum decision-makers, including authors and developers

Students of color learn and perform better when they see themselves and their experiences authentically and non-stereotypically reflected in their school curricula. What’s more, seeing a diverse set of people in books also helps white students develop a deeper understanding of their racial and ethnic identity and the world around them, which is filled with people of varying ethnicities and cultures.

In other words, we need more books with accurate portrayals of people of color, not fewer.